Rabbit courtesy of Wikipedia

Question: Who doesn’t love soft, snuggly, cute

little bunny rabbits?

Answer: Australia.

Now it’s not that Australians are particularly hard-hearted. Many an Australian child keeps rabbits as pets, but as an agricultural and environmental pest, the rabbit stands alone atop the heap.

Rabbit courtesy of

Wikipedia

Rabbits were successfully introduced by Thomas Austin in 1859. Red foxes had been introduced – for hunting – in 1855. While Australia abounded in game, wealthy new settlers were anxious to recreate the elite social pastime of sport hunting in their new home. Subsistence hunting was the domain of the aboriginal – for Australia’s transplanted Englishmen it was important to maintain a distinction between subsistence hunting, and hunting for sport, hence the rabbits.4

Once a successful colony of rabbits was established, they did what rabbits do best, they multiplied… rapidly. By the mid 1890s they would be a blight upon not only farmland, but pastoral and wilderness land as well. The grazier (rancher in American speak) who introduced them, said by way of explanation, “The introduction of a few rabbits could do little harm and might provide a touch of home, in addition to a spot of hunting.”2 It was hardly the statement Austin would want to be remembered for, but at first, rabbits seemed to be a very good idea.

To get an idea of just how fast the rabbit population grew, consider this: In 1867, just a bit over seven years from the time rabbits were introduced, Prince Albert, Duke of Edinburgh, became the first member of the royal family to visit Australia. Thomas Austin must have considered it quite an honor to host a hunt for the Prince.

It was a good hunt – the prince shot 415 rabbits in just three and a half hours. His assistants changed guns for him when the barrels became too hot.3 He was so delighted with the hunt that he stayed on to hunt again on the morrow. Austin may very well have congratulated himself for his wisdom in establishing a rabbit population.4

Two years later, at the end of his tour, the Prince returned to Barwon Park – Austin’s impressive estate. By then Austin’s neighbors were up in arms about the rabbits. Eventually they forced Austin to fence his property. It was too late, the voracious pests were already breeding outside the fence. Neighboring farmers tried many methods to control the rabbits – trapping, using ferrets, poisoning, building high stone fences, digging trenches lined with sharp debris, and hiring rabbiters. All was in vain. Rabbit damage was so bad it reduced land values in the Western District by one half.4

At first, the exploding rabbit population was a boon to many. The settlers happily added rabbit meat to their diet, and rabbit recipes abounded. Hatters began to use felt made from rabbit fur, and a rabbit canning industry sprouted.1 None of these rabbit culling activities – sport hunting, hunting for food, or trapping – had any noticeable affect on the growth of the rabbit population.

By the 1870s, thousands roamed Australia’s pastoral lands as rabbiters. The rabbit problem in New South Wales was so bad in the 1880s that a government bounty was offered for dead rabbits. It was withdrawn in 1887 (for fear of going broke) after claims were received for more than 25 million rabbit scalps.4

In 1896, at the government’s behest, Alfred Mason began a five month fact-finding assignment in the southeastern portion of Western Australia. He used camels as his transport across the rugged, bone-dry land. This proved prudent, even so he nearly perished. Upon his return, he recommended construction of several hundred miles of barrier fence along the state border.4,5

Rabbits

Using the Fence image courtesy of Wikipedia

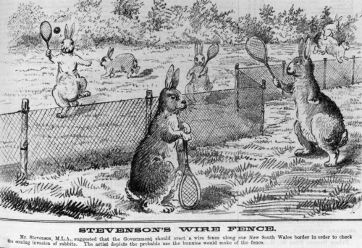

Long before Alfred Mason undertook his fact-finding mission, others had floated the idea of a fence for rabbits. Many mocked it (see 1884 cartoon above).6

In 1901, a Royal Commission ordered the building of a fence from the south coast of the state of Western Australia to Eighty Mile Beach in the northwest. It would become known as the No.1 Rabbit Proof Fence. When finished the fence stretched 1,139 miles – the longest line of unbroken fence in the world.5 Two additional fences were built at about the same time, and were designated Rabbit Proof Fence No.2 and No.3 respectively (see map). Finished in 1907, the three fences stretched for an astounding 2,023 miles.6 The No.2 fence was constructed upon discovering rabbits outside Fence No.1 in 1904. Fence No.3 was constructed later for the same reason.1

Rabbit

Fences Map image courtesy of Wikipedia

The last 70 miles of Fence No.1 was particularly difficult, taking over three years to build. During it’s construction its workforce consisted of 41 donkeys, 120 men, 210 horses, and 350 camels. The average load was transported 375 miles across a nearly waterless landscape – truly a remarkable accomplishment.5

The fence was constructed with wooden posts at 12’ on center, the posts extending 1’-9” into the soil and 4’-0” above it. Three 12 1/2 gauge plain wires were strung horizontally across the posts – one each at 4”, 1’-8”, and 3’-0” above the ground. Over those three plain backing wires, a wire netting was added, it extended six inches into the soil with three feet remaining above. In addition, a barbed wire was strung at 3’-9” above the ground. Later, two more wires were added near the top, one barbed and one plain, to deter foxes and dingos. Funnel traps were placed every 330 feet – to trap rabbits traveling along the fenceline.2

Rabbit Fence in

2005 image courtesy of Wikipedia

Upon completion, inspectors patrolled the fences under the direction of the Chief Inspector of Rabbits, Alexander Crawford. Chief Inspector of Rabbits, is without a doubt, one of the coolest job titles ever handed out. The boundary riders (inspectors) worked in pairs patrolling 124 mile sections of the fences. For transportation, inspectors first tried horses and bicycles. Next they tried autos, but the tires punctured too easily. They then tried camels, and they worked better. Ultimately they settled upon buckboard wagons pulled by camels. 1,5

The life of a boundary rider was no picnic. He didn’t simply ride along gazing at the fence. He had to do repairs, trim brush and trees, clean dead animals and debris from the fence, empty and clean the funnel traps, and set baited poisons. It was hard and lonely work under trying conditions.1In the end, the fence did not stop the rabbits. The pesky rodent continued to spread and multiply. Opinions of the fence’s effectiveness differ only as to how soon the fence was deemed ineffective. Some feel it was effective through the 1920s.

The fence, however, proved excellent protection against emus, hordes of which in times of drought, devastated farm crops. So the fence lives on today, little changed except for the use of modern materials. The working conditions of the boundary riders are better, thanks to air-conditioned vehicles and mobile phones.

The rabbit remains an abundant and destructive pest, although one that has been more effectively controlled through the intentional introduction of rabbit specific diseases.

It’s easy to mock Austin’s decision to create a rabbit population large enough for hunting. But Austin was no dunce. Others had experienced great difficulty trying to create just such a rabbit population. Austin’s careful analysis of previous failures led to his sucess. Who, in 1859, could have foreseen that once established, the rabbits would so completely take over their environment?

Rabbit populations had been established on nearby islands and were considered beneficial at best, and neutral at worst. Further, importing species from England was not something that was frowned upon. Thomas Austin was a product of his time, and should be judged in light of the attitudes and conditions of that time.

Sources for this article

copyright 2014 Almost Lucid Geezer

email

small.ice6205@fastmail DAWT com